Asia’s capital markets have changed dramatically since Asiamoney was first published in 1989. At the time, Asian borrowers hoping to raise dollars in the bond market had little choice but to sell yankee bonds, which were registered with the US Securities and Exchange Commission.

This was not always easy. Some US fund managers had to have countries like Malaysia and South Korea pointed out on a map, says one senior banker.

It also took a lot of legwork.

“You would have to go on a roadshow for maybe a week around the US to places like Minneapolis and Hartford, Connecticut,” recalls Stephen Williams, HSBC’s head of banking, southeast Asia.

“That would involve very intense interactions with investors. Then the following week you would go launch your bond and come back to Asia with what, by today’s standards, would be a modest-sized deal.”

The same situation applied in the loans market. A senior loans banker told Asiamoney about the hard work he put into a $100 million loan for an Indian borrower in the 1990s. That same borrower has since raised $3 billion in a single loan.

As for the IPO market, in the early 1990s it had the air of the Wild West, with investors able to buy a wide variety of deals, from the market-opening privatizations of Chinese state-owned enterprises to the listing of obscure mango companies in the Philippines, says one senior equity capital markets banker.

It is hard to pinpoint when the Asia Pacific markets really changed and started to look more like they do today, but July 1997 is a good place to begin because of two momentous events.

Chain reaction

The UK handed free-wheeling Hong Kong back to communist China at the stroke of midnight on June 30/July 1. And on July 2, Thailand’s central bank decided to abandon the baht’s peg to the dollar, realizing it could no longer keep speculators at bay because its foreign currency reserves were running out.

In the days that followed, the Thai currency continued to fall against the dollar, setting off a chain reaction of events that soon affected everybody in Asia: other Asian currencies came under enormous pressure, stock markets collapsed and spreads in the bond market widened dramatically.

| Fred Hu, Primavera Capital |

Almost every country in the region was damaged by the Asian financial crisis. It brought the main sources of business for global investment banks in Asia – southeast Asia and the Asian tigers – to their knees. But it marked a turning point for China, after which Chinese deals rose in size, prominence and profitability.

In the space of barely 20 years, China has left the sidelines and now accounts for about two thirds of the business in Asia’s debt and equity markets. That development has turned Hong Kong into the premier financial hub of the region.

Fred Hu, who joined Goldman Sachs in 1997 and rose to the position of chairman for Greater China at the firm, was behind many of China’s billion-dollar privatizations, so he was well-placed to observe Hong Kong’s transformation.

“At one point in the mid 1990s, the market capitalization of the Hong Kong stock exchange was less than that of General Motors,” says Hu. “That shows its status then in the global financial system.”

Hu, who later founded investment firm Primavera Capital, remembers 1997 not just for the handover or the beginning of the Asian financial crisis, but for his and Hong Kong’s first landmark IPO – China Telecom (Hong Kong). Now called China Mobile, the company did a dual listing in Hong Kong and New York for $4.23 billion.

“The IPO built China Inc’s credibility in the international capital markets and put China on investors’ radar screens,” says Hu. “Up until then, China had been on the periphery as an emerging market. Today China Mobile is thought of as a dividend stock, but back when it listed, it was a must-own growth story. It was at the very start of the ICT [information and communications technology] revolution.”

But China Mobile got off to a rocky start.

“When the deal was done, it coincided with the eruption of the Asian financial crisis,” says Hu. “So the markets were very volatile – the stabilization agents were using any power they could to keep the stock price steady.”

A stream of record-breaking privatizations followed, including from the energy sector, telecoms and financial services, giving a boost to Hong Kong’s fortunes.

Before the Asian financial crisis, business had boomed in the region’s emerging markets. Hong Kong was regarded as a colonial stomping ground with little up for grabs. Countries such as India, Malaysia and Indonesia were opening up, their governments boosting volumes with a wave of privatizations.

“The Asian financial crisis shook the foundations of that,” says Udhay Furtado, head of ECM, Asia ex-Greater China at Citi. “The markets that were worst hit were those that were the most open, which were all of the southeast Asian markets – Indonesia, Thailand and the Philippines being the centre of that storm.”

China Mobile’s IPO built China Inc’s credibility in the international capital markets and put China on investors’ radar screens - Fred Hu, Primavera Capital

Many of those countries (as well as a lot of companies from those countries) had gorged on dollar bonds, so the collapse of Asian currencies meant these borrowers struggled to repay their dollar-denominated debts. The IMF had to bail out several countries, while scores of companies across Asia defaulted on their debts and went bankrupt. Korea, for example, turned from a country of bond-issuing conglomerates to one of defaults and mass unemployment; in early 1998, the government issued a nationwide call for its citizens to donate their gold to help it repay a $21 billion loan from the IMF.

The Asian crisis led to big changes in the financial landscape. Dozens of domestic Asian banks, hit by debt, either collapsed and were shut down, or else had to be rescued and bailed out by new owners. The merchant banks that had regarded Hong Kong as their home turf also faced problems, in some cases even before the crisis blew up: Barings was brought down by Singapore-based trader Nick Leeson in 1995, and later bought by ING for a pound, while a trading scandal at Jardine Fleming led to the removal of the top brass and fines from the regulators. The firm was swallowed up by JPMorgan a few years later.

Hong Kong startup Peregrine Investments was felled in 1998, thanks to its over-exposure to a heavily indebted Indonesian taxi company called Steady Safe.

Gateway

As an increasing number of privately owned Chinese companies turned offshore for equity and debt fundraising, big US and European banks began boosting or creating operations in Hong Kong; that helped to give an initial lift to Asia Pacific’s loans business, says one senior Hong Kong-based loans banker. But in contrast to the debt and equity capital markets, where western banks have tended to dominate, Australian and Japanese banks were traditionally seen as the powerhouses in Asia’s offshore market.

In the early 2000s, global institutional investors began opening offices in the region.

“After 2004, most of the large IPOs from China were in Hong Kong only,” says a seasoned former ECM banker in Hong Kong. “As Hong Kong grew on the primary side, you started to see a lot more foreign capital establishing itself in Hong Kong as a gateway to China.

“The big funds started to deploy more research analysts here and there were more and more retail and institutional products here for investors, from these big international companies, so the pool of capital started to get bigger here,” the banker adds. “That is partly why as a local company you didn’t need a listing in the US anymore. You had the capital, and you had the bid, in Hong Kong.”

In Asia we’ve always had a very strong local bank market, in every market, but it’s only the Chinese banks that have managed in more recent times to make it into the top 10 - Henrik Raber, Standard Chartered

The investor pool became sufficiently deep in the debt markets, too. The phenomenon helped drive a growth in bond issuance, which by the 2000s was rivalling bank lending.

“In the late 90s and going into the 2000s, you would have a team of a few people in Hong Kong or Singapore and you would work on maybe four or five bond deals a year,” says a Hong Kong-based head of debt at a European bank. “Then by 2004 or 2005, we were doing that many every week.”

Bankers partly had China to thank for an increase in issuance, although borrowers from elsewhere in the region were still printing bonds. But China really took the lead in the bond market after the global financial crisis; it went from 7% of deal flow in the Asia Pacific ex-Japan bond market in 2008, to 14% the following year, based on the number of deals.

A decade later, in 2018, Chinese deals represented 54% of the total, according to Dealogic data.

Phenomenon

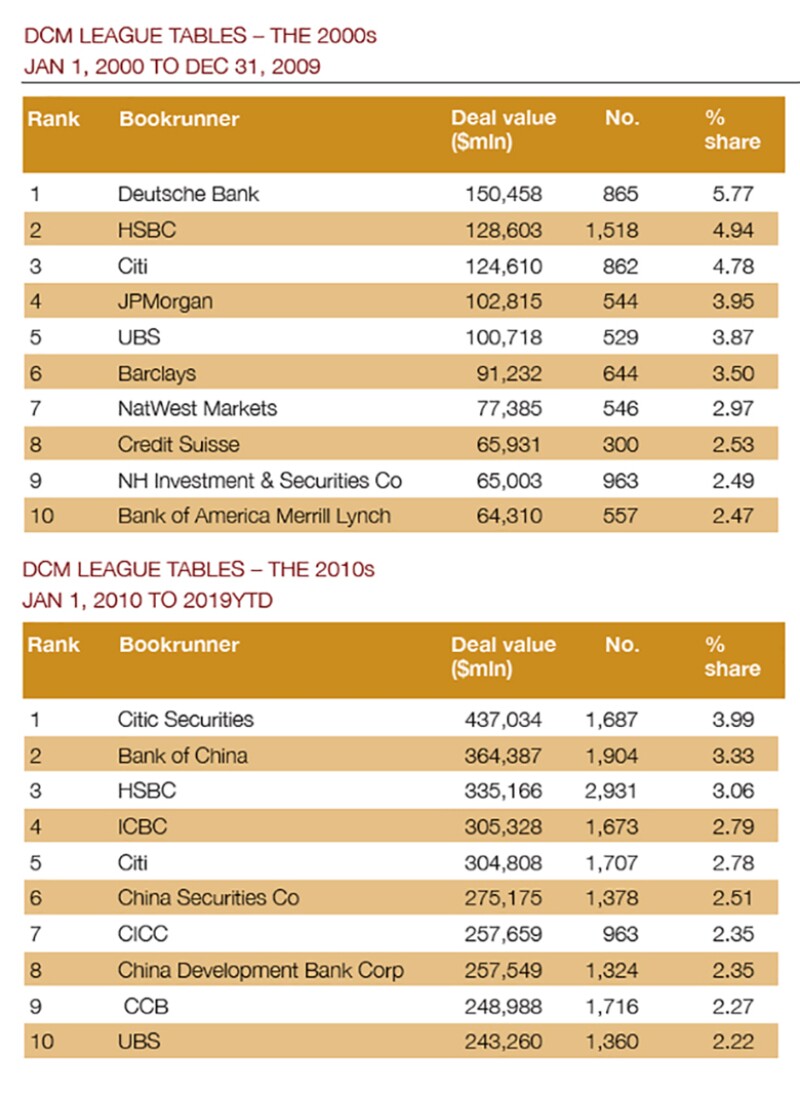

With the rise of Chinese borrowers, China’s banks and securities houses grew more ambitious for a share of the business. As Henrik Raber, global head of credit markets at Standard Chartered, sees it, what Chinese underwriters have pulled off is unique in the region.

“In Asia we’ve always had a very strong local bank market, in every market, but it’s only the Chinese banks that have managed in more recent times to make it into the top 10, and they are doing that at quite a rapid pace,” he says.

|

Henrik Raber, |

“There are some very sizeable banks that are now becoming deep in the underwriting of bonds and equities, and they have very significant operations and balance sheets.”

The phenomenon started with Chinese underwriters assisting their client base, adds Raber, but as they have added depth to their capabilities, “their aspirations have broadened beyond China. I think they are still quite regionally focused but this is a change that is here to stay.”

The big US banks have also changed tack.

“What has happened over the past 20 years is the dominance we once saw among US investment banks in the debt capital markets has gone from them being at the top of the league tables around the mid 2000s, to them being very targeted on a few deals – not prioritizing league tables, but caring more about doing a few deals for their best and brightest customers,” says HSBC’s Williams.

It has become a cliché among global banks to hear that they no longer care about their league table position, even when they really do. But while competition for league table slots might have waned a little, these rankings still serve a purpose for borrowers and for management based elsewhere.

“Anybody can appoint by mistake someone to do one or two deals, but if you are doing 50 deals a year in a particular market and you are near the top or at the top of the league tables, it probably gives you an indication that you are quite competent,” says John Corrin, global head of loan syndications at ANZ.

The Asia Pacific loan market is still dominated by international banks, with Bank of China creeping into the top 10 over the past 30 years.

But a different kind of change has taken place in the loan market, and perhaps every market, since the global financial crisis.

“There is a lot less business done in pubs,” says one debt banker in Hong Kong. “The old idea of taking people along and getting them drunk or whatever else, I’m not saying it doesn’t happen, but it is happening a lot, lot less than it used to.

Diverse

These days, the markets are far more diverse as various local currency markets have taken off, says Corrin. Local markets have become more sophisticated; 20 years ago there were no large deals, by today’s standards, in Thai baht or Indonesian rupiah and there was no renminbi lending of any significance, for example.

But as emerging market economies have developed in the region, many local currency markets have matured with them.

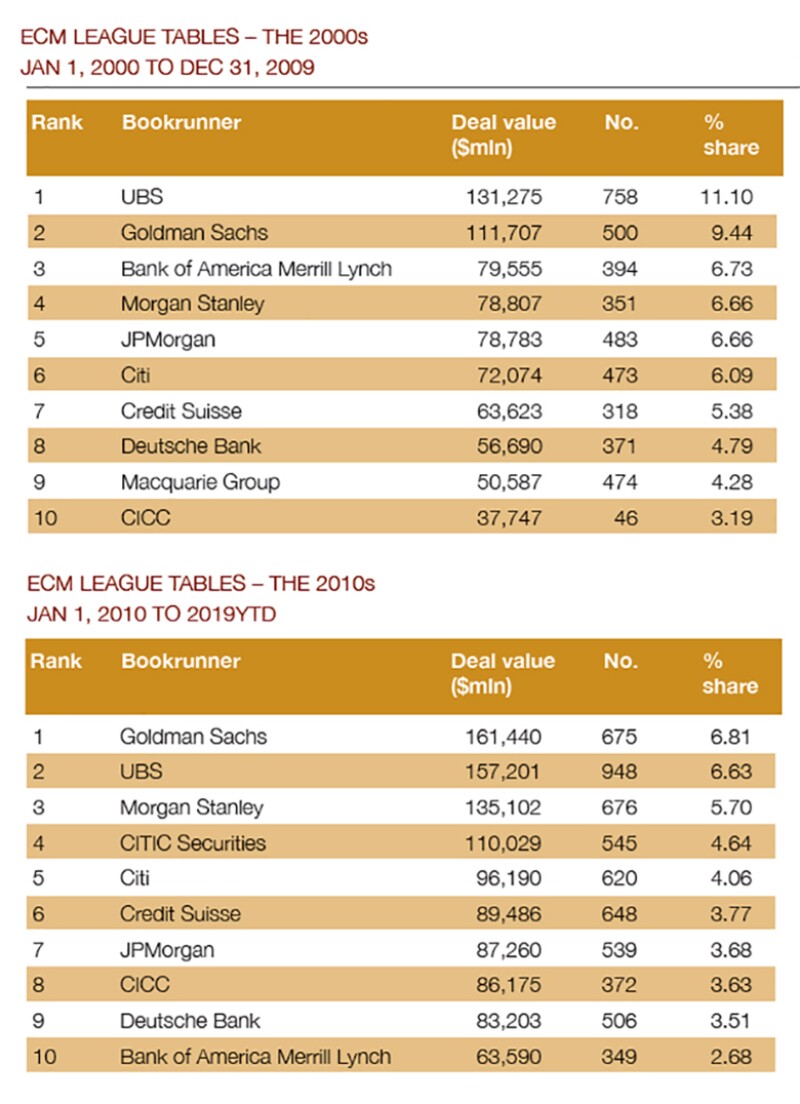

The M&A advisory business, like that of the loan market, is filled with international names, reflecting the global nature of the work. The largest transactions in Asia Pacific over the last three decades are between counterparties from around the world. US investment banks, such as Goldman Sachs and Morgan Stanley, have tended to lead M&A advisory in Asia Pacific, although UBS has always been a strong player. But from mainland China, only CICC has made its way into the top 10.

Some bankers say the lack of regional advisers is due to many Asian businesses still being owned by their founders or by the second generation, so they are more focused on expanding rather than merging or succumbing to a leveraged buyout. As a result, leveraged finance also makes up just a small part of the loan market.

As it happens, the biggest acquisition of the 2000s was executed by the company behind Asia Pacific’s largest IPO from the previous decade, China Telecom (HK). The latter took over China Mobile Communications Corp in a 100% buyout for $32.8 billion.

China’s state-owned enterprises (SOEs) are still making a splash in the global M&A market, among the top 10 of the 2010 M&A deals. But the largest deal in the market so far this decade involved Chinese technology firm Qihoo 360 Technology.

The internet security firm used the frowned-upon practice of a back-door listing – when a private company merges with a typically much smaller entity that is already trading on a stock exchange.

That deal illustrated one key change in the market over the last three decades: after making the most of the international capital markets, China is now trying to move business closer to home. Qihoo 360 de-listed from the New York Stock Exchange and was ‘acquired’ by Shanghai-based lift maker SJEC Corp in 2017 through a $61 billion deal. It now trades on the Shanghai Stock Exchange.

Hong Kong still remains the destination of choice for the bulk of IPO hopefuls in Asia. Where it was once an old economy hub, the 2010s and in particular the last 18 months have seen a deluge of new economy issuers listing in the city.

The crowning moment came for the Hong Kong Exchange’s chief executive Charles Li when news emerged in May this year that NYSE-listed Alibaba plans to float on the HKEx.

Li responded with glee on hearing the news: “Welcome home!”

Fees: Lower by the day

Across the capital markets, fees have fallen and syndicates have become bigger in Asia Pacific over the last three decades. Once upon a time, the sell side was a smaller place, with deals often handled by a single bank, or a lead with a handful of co-managers. Also, with fewer transactions to handle, the fees were higher.

In the 1990s, bond deals had one firm, typically a US investment bank, running the book-building process, says Stephen Williams, HSBC’s head of global capital markets, Asia Pacific.

“They would get 75% to 80% of the economics, and then you would have two or three co-managers, who would again be a US investment bank,” he says. “They would get 15% to 20% of the economics, but they wouldn’t really drive the deal. They might have visibility of the pot but typically a passive role.”

How times have changed. As John Corrin, global head of loan syndications at ANZ, points out, almost every market has become more competitive, while fewer issuers are prepared to entrust a deal to only one bank in the wake of the global financial crisis.

“In the good days, you would get a deal on your own, and as a result of that the revenue outcome for the banks was very different,” he says. “Nowadays you may get a deal split between multiple banks and the fee pot has shrunk compared to 12 years ago.”

Corporate treasurers or chief financial officers in Asia have also become a lot more sophisticated, adds Corrin: “They are not doing their first deals, they have been in the trade for 10 to 20 years themselves. They know exactly how the system works. They know what they have to pay for and what they don’t have to pay for.”

In equity capital markets, syndicate teams have suffered a unique loss of deal revenue because of the technique used by many Chinese issuers. Fees were as much as 30% higher 20 years ago and there were fewer bookrunners on each deal, but in the last decade the phenomenon of ‘friends and family’ trades – where investors are in some way linked to an issuer from outside the typical book-building process – has emerged.

“You have a tranche of the deal carved out where the issuers decide where the shares are going,” says a seasoned former ECM banker in Hong Kong.

“And because they found that demand, they don’t want to pay you for it. The Chinese banks were often the gateway to finding those friends and family.”

China's SOEs in ECM action

The dual listing by China Telecom (Hong Kong) in Hong Kong and New York in 1997, worth a chunky $4.23 billion, was a game changer for the markets and was followed by a host of big-ticket privatizations of Chinese state-owned assets: China Petroleum & Chemical Corp, better known as Sinopec, and China Unicom in 2000; Bank of China and ICBC in 2006; and PetroChina in 2007 were just some of the big names that captured the attention of international investors.

“In the early 2000s, China started to privatize the SOEs and that was really the start of the opening up and benchmarking of China,” says Udhay Furtado, head of ECM, Asia ex-Greater China, at Citi. “There were few large, liquid, internationally traded China stocks before that, aside from the main Hong Kong names.”

But many of China’s SOEs needed some serious whipping into shape before they could be eligible for listing on an international exchange.

The country’s financial institutions posed some of the biggest challenges, which former Goldman Sachs veteran banker Fred Hu remembers well from his time preparing Bank of Communications for its HK$14.65 billion ($1.87 billion) Hong Kong IPO in 2005.

“My team and I spent three years advising Bank of Communications on its restructuring to prepare for its IPO, the very first-ever listing of a mainland bank in the international market,” says Hu. “The bank had a high level of bad assets, the organization was a mess, with virtually no distinction between the front office, middle office or back office. The IT system was primitive. There was weak internal control and poor risk management.”

But Bank of Communications overcame all the challenges to list successfully.

China’s gradual rise through the 2000s followed a circuitous process, adds Furtado. “It was a virtuous circle: you start to privatize, raise liquidity and investor following, increase index benchmarks, which further drives investor activity.”

Given the large number of SOEs in China, the privatization process is still in full swing, with telecom infrastructure company China Tower raising HK$54 billion in Hong Kong’s largest IPO last year. Others in the pipeline include SinoChem Energy and Sinopec Marketing, both expected to list via multi-billion-dollar deals.

China’s privately owned companies also started to join the flow of business into Hong Kong nice and early. Tencent Holdings was an early adopter, listing in the city for HK$1.55 billion in 2004.